Strengthening your domain

2010. Jimmy Bogard.

toc

- primer

- aggregate-roots

- aggregate-construction

- encapsulated-collections

- encapsulating-operations

- the-double-dispatch-pattern

- no-silver-domain-modeling-bullets

article series

- Services in Domain-Driven Design

- primer

- Aggregate Construction

- Encapsulated collections

- Encapsulating operations

- The double dispatch pattern

- No silver domain modeling bullets

- 10 Lessons from a Long Running DDD Project: 1, 2

services

Services are first-class citizens of the domain model. When concepts of the model would distort any Entity or Value Object, a Service is appropriate.

A good Service has these characteristics:

- The operation relates to a domain concept that is not a natural part of an Entity or Value Object

- The interface is defined in terms of other elements in the domain model

- The operation is stateless

Services are always exposed as an interface, not for “swappability”, testability or the like, but to expose a set of cohesive operations in the form of a contract. On a sidenote, it always bothered me when people say that an interface with one implementation is a design smell. No, an interface is used to expose a contract. Interfaces communicate design intent, far better than a class might.

But most examples I see of Services are something trivial, such as IEmailSender. But Services exist in most layers of the DDD layered architecture: Application, Domain, Infrastructure.

An Infrastructure Service would be something like our IEmailSender, that communicates directly with external resources, such as the file system, registry, SMTP, database, etc. Something like NHibernate would show up in the Infrastructure.

Domain services are the coordinators, allowing higher level functionality between many different smaller parts. These would include things like OrderProcessor, ProductFinder, FundsTransferService, and so on. Since Domain Services are first-class citizens of our domain model, their names and usages should be part of the Ubiquitous Language. Meanings and responsibilities should make sense to the stakeholders or domain experts.

In many cases, the software we write is replacing or supplementing a human’s job, such as Order Processor, so it’s often we find inspiration in the existing business process for names and responsibilities. Where an existing name doesn’t fit, we dive into the domain to try and surface a hidden concept with the domain expert, which might have existed but didn’t have a name.

Finally, we have Application Services. In many cases, Application Services are the interface used by the outside world, where the outside world can’t communicate via our Entity objects, but may have other representations of them. Application Services could map outside messages to internal operations and processes, communicating with services in the Domain and Infrastructure layers to provide cohesive operations for outside clients. Messaging patterns tend to rule Application Services, as the other service layers don’t have a reference back out to the Application Services. Business rules are not allowed in an Application Service, those belong in the Domain layer.

In top-down design, we typically start from the Application or Domain Service, defining the actual interface clients use, then use TDD to drive out the implementation. As we’re always starting from the client perspective with actual client scenarios, we get a high degree of confidence that what we’re building will create success and add value. When stories are vertical slices of functionality, this is fairly straightforward, at least mechanically so.

I used to make the mistake of dismissing Services as a necessary evil, I’ve started to realize the potential the Application and Domain services have in creating a well-designed model.

primer

Code smells

A lot of DDD is just plain good OO programming. Unit tests and code smells are the best indication that our domain is wrong, along with conversations with our domain experts. In systems that start to move beyond merely CRUD, specific code smells start to surface that should indicate that our system is starting to accumulate behavior, but it just might not be in the right place. In a behavior-rich, but anemic domain, the domain is surrounded by a multitude of services that do the actual work, and fiddle with state on our domain objects. The domain objects contain state to be persisted, but it’s not the domain objects themselves exposing any operations. But this is just code smell! Lots of code smells indicate that our domain is not as rich as at could be. The behavior is out there, but just needs to be moved around. Some smells I look for include:

- Primitive Obsession

- Data Class

- Inappropriate Intimacy

- Lazy Class

- Feature Envy

- Middle Man

All these are smells between classes, where usually a domain service is waaaay to concerned with a set of entities, when behavior could just be moved down into those entities.

Aggregate Roots

One of the most quoted, but most misunderstood ideas in DDD is the concept of aggregate roots. But what is this aggregate root? Is it just an entity with a screen in front of it? A row in a database? Evans defined a set of rules for Aggregates:

- The root Entity has global identity and is ultimately responsible for checking invariants

- Entities inside the boundary have local identity, unique only within the Aggregate.

- Nothing outside the Aggregate boundary can hold a reference to anything inside, except to the root Entity. The root Entity can hand references to the internal Entities to other objects, but they can only use them transiently (within a single method or block).

- Only Aggregate Roots can be obtained directly with database queries. Everything else must be done through traversal.

- Objects within the Aggregate can hold references to other Aggregate roots.

- A delete operation must remove everything within the Aggregate boundary all at once

- When a change to any object within the Aggregate boundary is committed, all invariants of the whole Aggregate must be satisfied.

- It’s a lot, but I generally think of Aggregate roots as consistency boundaries. When I interact with an Aggregate, its invariants must always be satisfied. Keeping invariants satisfied strengthens the design and responsibility of the objects, as the logic that defines the Aggregate is then self-contained.

Strategic Design

We may not like it, but not all of our system’s model will ever reach our vision of perfection. Which is fine, as a perfect model across our entire system would be prohibitively expensive with little ROI on all that work. Instead, we have to focus on specific areas of the core domain that provide the most value to the customer. The better our core domain model, the better our system represents the conceptual model we’ve defined with our customers, and the better we will be able to serve their needs.

Unfortunately, all the interesting Strategic Design chapters are after the basic DDD patterns in the book, so that many folks get lost discussing repositories, entities, aggregates and so on. But in recent interviews, Evans mentions that these later discussions are more important than the earlier ones. The bottom line is that we have to choose carefully where we spend our time refining our domain model. Some areas will not be as refined as others, but that’s perfectly acceptable. The trick is to find which areas will give us the most value for our time spent in refactoring, refinement and modeling. Finally, it’s worth noting that there is no “best” design. There is only the best design given our current understanding. Software development is a process of discovery, where concepts that seemed unimportant or hidden may suddenly become obvious and critical later. That’s still normal, and not a negative thing. Lots of concepts around an idea will be thrown around, but only the most important ones will rise to the top, and sometimes that just takes time.

Aggregate Construction

Our application complexity has hit its tipping point, and we decide to move past anemic domain models to rich, behavioral models. But what is this anemic domain model? Let’s look at Fowler’s definition, now over 6 years old:

The basic symptom of an Anemic Domain Model is that at first blush it looks like the real thing. There are objects, many named after the nouns in the domain space, and these objects are connected with the rich relationships and structure that true domain models have. The catch comes when you look at the behavior, and you realize that there is hardly any behavior on these objects, making them little more than bags of getters and setters. Indeed often these models come with design rules that say that you are not to put any domain logic in the the domain objects. Instead there are a set of service objects which capture all the domain logic. These services live on top of the domain model and use the domain model for data.

For CRUD applications, these “domain services” should number very few. But as the number of domain services begins to grow, it should be a signal to us that we need richer behavior, in the form of Domain-Driven Design. Building an application with DDD in mind is quite different than Model-Driven Architecture. In MDA, we start with database table diagrams or ERDs, and build objects to match. In DDD, we start with interactions and behaviors, and build models to match. But one of the first issues we run into is, how do we create entities in the first place? Our first unit test needs to create an entity, so where should it come from?

Creating Valid Aggregates

Validation can be a tricky beast in applications, as we often see validation has less to do with data than it does with commands. For example, a Person might have a required “BirthDate” field on a screen. But we then have the requirement that legacy, imported Persons might not have a BirthDate. So it then becomes clear that the requirement of a BirthDate depends on who is doing the creation.

But beyond validation are the invariants of an entity. Invariants are the essence of what it means for an entity to be an entity. We may ask our customers, can a Person be a Person (in our system) without a BirthDate? Yes, sometimes. How about without a Name? No, a Person in our system must have some identifying features, that together define this “Person”. An Order needs an OrderNumber and a Customer. If the business got a paper order form without customer information, they’d throw it out! Notice this is not validation, but something else entirely. We’re asking now, what does it mean for an Order to be an Order? Those are its invariants.

Suppose then we have a rather simple set of logic. We indicate our Orders as “local” if the billing province is equal to the customer’s province. Rather easy method:

public class Order

{

public bool IsLocal()

{

return Customer.Province == BillingProvince;

}

I simply interrogate the Customer’s province against the Order’s BillingProvince. But now I can get myself into rather odd situations:

[Test]

public void Should_be_a_local_customer_when_provinces_are_equal()

{

var order = new Order

{

BillingProvince = "Ontario"

};

var customer = new Customer

{

Province = "Ontario"

};

var isLocal = order.IsLocal();

isLocal.ShouldBeTrue();

}

Instead of a normal assertion pass/fail, I get a NullReferenceException! I forgot to set the Customer on the Order object.

But wait – how was I able to create an Order without a Customer? An Order isn’t an Order without a Customer, as our domain experts explained to us. We could go the slightly ridiculous route, and put in null checks.

But wait – this will never happen in production. We should just fix our test code and move on, right? Yes, I’d agree if you were building a transaction-script based CRUD system (the 90% case). However, if we’re doing DDD, we want to satisfy that requirement about aggregate roots, that its invariants must be satisfied with all operation. Creating an aggregate root is an operation, and therefore in our code “new” is an operation. Right now, invariants are decidedly not satisfied.

Let’s modify our Order class slightly:

public class Order

{

public Order(Customer customer)

{

Customer = customer;

}

We added a constructor to our Order class, so that when an Order is created, all invariants are satisfied. Our test now needs to be modified with our new invariant in place:

[TestFixture]

public class Invariants

{

[Test]

public void Should_be_a_local_customer_when_provinces_are_equal()

{

var customer = new Customer

{

Province = "Ontario"

};

var order = new Order(customer)

{

BillingProvince = "Ontario"

};

var isLocal = order.IsLocal();

isLocal.ShouldBeTrue();

}

}

And now our test passes!

Summary and alternatives

Going from a data-driven approach, this will cause pain. If we write our persistence tests first, we run into “why do I need a Customer just to test Order persistence?” Or, why do we need a Customer to test order totalling logic? The problem occurs further down the line when you start writing code against a domain model that doesn’t enforce its own invariants. If invariants are only satisfied through domain services, it becomes quite tricky to understand what a true Order is at any time. Should we always code assuming the Customer is there? Should we code it only when we “need” it?

If our entity always satisfies its invariants because its design doesn’t allow invariants to be violated, the violated invariants can never occur. We no longer need to even think about the possibility of a missing Customer, and can build our software under that enforced rule going forward. In practice, I’ve found this approach actually requires less code, as we don’t allow ourselves to get into ridiculous scenarios that we now have to think about going forward.

But building entities through a constructor isn’t the only way to go. We also have:

The bottom line is – if our entity needs certain information for it to be considered an entity in its essence, then don’t let it be created without its invariants satisfied!

Encapsulated collections

One of the common themes throughout the DDD book is that much of the nuts and bolts of structural domain-driven design is just plain good use of object-oriented programming. This is certainly true, but DDD adds some direction to OOP, along with roles, stereotypes and patterns. Much of the direction for building entities at the class level can, and should, come from test-driven development. TDD is a great tool for building OO systems, as we incrementally build our design with only the behavior that is needed to pass the test. Our big challenge then is to write good tests.

To fully harness TDD, we need to be highly attuned to the design that comes out of our tests. For example, suppose we have our traditional Customer and Order objects. In our world, an Order has a Customer, and a Customer can have many Orders. We have this directionality because we can navigate this relationship from both directions in our application. In the last post, we worked to satisfy invariants to prevent an unsupported and nonsensical state for our objects.

We can start with a fairly simple test:

[Test]

public void Should_add_the_order_to_the_customers_order_lists_when_an_order_is_created()

{

var customer = new Customer();

var order = new Order(customer);

customer.Orders.ShouldContain(order);

}

At first, this test does not compile, as Customer does not yet contain an Orders member. To make this test compile (and subsequently fail), we add an Orders list to Customer:

public class Customer

{

public string FirstName { get; set; }

public string LastName { get; set; }

public string Province { get; set; }

public List<Order> Orders { get; set; }

public string GetFullName()

{

return LastName + ", " + FirstName;

}

}

With the Orders now exposed on Customer, we can make our test pass from the Order constructor:

public class Order

{

public Order(Customer customer)

{

Customer = customer;

customer.Orders.Add(this);

}

And all is well in our development world, right? Not quite. This design exposes quite a bit of functionality that I don’t think our domain experts need, or want. The design above allows some very interesting and very wrong scenarios:

[Test]

public void Not_supported_situations()

{

// Removing orders?

var customer1 = new Customer();

var order1 = new Order(customer1);

customer1.Orders.Remove(order1);

// Clearing orders?

var customer2 = new Customer();

var order2 = new Order(customer1);

customer2.Orders.Clear();

// Duplicate orders?

var customer3 = new Customer();

var customer4 = new Customer();

var order3 = new Order(customer3);

customer4.Orders.Add(order3);

}

With the API I just created, I allow a number of rather bizarre scenarios, most of which make absolutely no sense to the domain experts:

- Clearing orders

- Removing orders

- Adding an order from one customer to another

- Inserting orders

- Re-arranging orders

- Adding an order without the Order’s Customer property being correct

This is where we have to be a little more judicious in the API we expose for our system. All of these scenarios are possible in the API we created, but now we have some confusion on whether we should support these scenarios or not. If I’m working in a similar area of the system, and I see that I can do a Customer.Orders.Remove operation, it’s not immediately clear that this is a scenario not actually coded for. Worse, I don’t have the ability to correctly handle these situations if the collection is exposed directly.

Suppose I want to clear a Customer’s Orders. It logically follows that each Order’s Customer property would be null at that point. But I can’t hook in easily to the List

Moving towards intention-revealing interfaces

Let’s fix the Customer object first. It exposes a List

public class Customer

{

private readonly IList<Order> _orders = new List<Order>();

public string FirstName { get; set; }

public string LastName { get; set; }

public string Province { get; set; }

public IEnumerable<Order> Orders { get { return _orders; } }

public string GetFullName()

{

return LastName + ", " + FirstName;

}

}

This interface explicitly tells users of Customer two things:

- Orders are readonly, and cannot be modified through this aggregate

- Adding orders are done somewhere else

I now have the issue of the Order constructor needing to add itself to the Customer’s Order collection. I want to do this:

public class Order

{

public Order(Customer customer)

{

Customer = customer;

customer.AddOrder(this);

}

Instead of exposing the Orders collection directly, I work through a specific method to add an order. But, I don’t want that AddOrder available everywhere, I want to only support the enforcement of the Order-Customer relationship through this explicitly defined interface. I’ll do this by exposing an AddOrder method, but exposing it as internal:

public class Customer

{

private readonly IList<Order> _orders = new List<Order>();

public string FirstName { get; set; }

public string LastName { get; set; }

public string Province { get; set; }

public IEnumerable<Order> Orders { get { return _orders; } }

internal void AddOrder(Order order)

{

_orders.Add(order);

}

}

There are many different ways I could enforce this relationship, from exposing an AddOrder method publicly on Customer or through the approach above. But either way, I’m moving towards an intention-revealing interface, and only exposing the operations I intend to support through my application. Additionally, I’m ensuring that all invariants of my aggregates are satisfied at the completion of the Create Order operation. When I create an Order, the domain model takes care of the relationship between Customer and Order without any additional manipulation.

If I publicly expose a collection class, I’m opening the doors for confusion and future bugs as I’ve now allowed my system to tinker with the implementation details of the relationship. It’s my belief that the API of my domain model should explicitly support the operations needed to fulfill the needs of the application and interaction of the UI, but nothing more.

Encapsulating operations

In previous posts, we walked through the journey from an intentionally anemic domain model (one specifically designed with CRUD in mind), towards a design of a stronger domain model design. Many of the comments on twitter and in the posts noted that many of the design techniques are just plain good OO design. Yes! That’s the idea. If we have behavior in our system, it might not be in the right place. The DDD domain design techniques are in place to help move that behavior from services surrounding the domain back into the domain model where it belongs.

Besides managing the creation of aggregates and relationships inside and between aggregate roots, there comes the point where we need to actually…update information in our domain model. One of the tipping points from moving from a CRUD model to a DDD model is emergent complexity in updating information in our model.

Fees and Payments

Let’s suppose that in our domain we can levy Fees against Customers. Later, Customers can make Payments on those Fees. At any time, I can look up a Fee and determine the Fee’s balance. Or, I can look up all the Customer’s Fees, and see a list of all the Fee’s balances. Based on the previous posts, I might end up with something like this:

[Test]

public void Should_apply_the_fee_to_the_customer_when_charging_a_customer_a_fee()

{

var customer = new Customer();

var fee = customer.ChargeFee(100m);

fee.Amount.ShouldEqual(100m);

customer.Fees.ShouldContain(fee);

}

The ChargeFee method is rather straightforward:

public Fee ChargeFee(decimal amount)

{

var fee = new Fee(amount, this);

_fees.Add(fee);

return fee;

}

Next, we want to be able to apply a payment to a fee:

[Test]

public void Should_be_able_to_record_a_payment_against_a_fee()

{

var customer = new Customer();

var fee = customer.ChargeFee(100m);

var payment = fee.AddPayment(25m);

fee.RecalculateBalance();

payment.Amount.ShouldEqual(25m);

fee.Balance.ShouldEqual(75m);

}

We store a calculated balance, as this gives us much better performance, querying abilities and so on. It’s rather easy to make this test pass:

public Payment AddPayment(decimal paymentAmount)

{

var payment = new Payment(paymentAmount, this);

_payments.Add(payment);

return payment;

}

public void RecalculateBalance()

{

var totalApplied = _payments.Sum(payment => payment.Amount);

Balance = Amount - totalApplied;

}

However, our test looks rather strange at this point. We have a method to establish the relationship between Fee and Payment (the AddPayment method), which acts as a simple facade over the internal list. But what’s with that extra RecalculateBalance method? In many codebases, that ‘RecalculateBalance’ method would be in a BalanceCalculationService, reinforcing an anemic domain.

But we can do one better. Isn’t the act of recording a payment a complete operation? In the real physical world, when I give a person money, the entire transaction is completed as a whole. Either it all completes successfully, or the transaction is invalid. In our example, how can I add a payment and the balance not be immediately updated? It’s rather confusing to have to “remember” to use these extra calculation services and helper methods, just because our domain objects are too dumb to handle it themselves.

Thinking with commands

When we called the AddPayment method, we left our Fee aggregate root in an in-between state. It had a Payment, yet its balance was incorrect. If Fees are supposed to act as consistency boundaries, we’ve violated that consistency with this invalid state. Looking strictly through a code smell standpoint, this is the Inappropriate Intimacy code smell. Inappropriate Intimacy is one of the biggest indicators of an anemic domain model. The behavior is there, but just in the wrong place.

But we can help ourselves to enforce those aggregate boundaries with encapsulation. Not just encapsulation like properties encapsulate fields, but encapsulating the operation of recording a fee. Even the name of AddPayment could be improved, to RecordPayment. The act of recording a payment in the Real World involves adding the payment to the ledger and updating the balance book. If the accountant solely adds the payment to the ledger, but does not update the balance book, they haven’t yet finished recording the payment. Why don’t we do the same? Here’s our modified test:

[Test]

public void Should_be_able_to_record_a_payment_against_a_fee()

{

var customer = new Customer();

var fee = customer.ChargeFee(100m);

var payment = fee.RecordPayment(25m);

payment.Amount.ShouldEqual(25m);

fee.Balance.ShouldEqual(75m);

}

We got rid of that pesky, strange extra Recalculate call, and now encapsulated the entire command of “Record this payment” to our aggregate root, the Fee object. The RecordPayment method now encapsulates the complete operation of recording a payment, ensuring that the Fee root is self-consistent at the completion of the operation:

public Payment RecordPayment(decimal paymentAmount)

{

var payment = new Payment(paymentAmount, this);

_payments.Add(payment);

RecalculateBalance();

return payment;

}

private void RecalculateBalance()

{

var totalApplied = _payments.Sum(payment => payment.Amount);

Balance = Amount - totalApplied;

}

Notice that we’ve also made the Recalculate method private, as this is an implementation detail of how the Fee object keeps the balance consistent. From someone using the Fee object, we don’t care how the Fee object keeps itself consistent, we only want to care that it is consistent.

The public contour of the Fee object is simplified as well. We only expose operations that we want to support, captured in the names of our ubiquitous language. The “How” is encapsulated behind the aggregate root boundary.

Wrapping it up

We again see that a consistent theme in DDD is good OO and attention to code smells. DDD helps us by giving us patterns and direction, towards placing more and more logic inside our domain. The difference between an intentionally anemic domain model (a persistence model) and an anemic domain model is the presence of these code smells. If you don’t have a legion of supporting services propping up the state of your domain model, then there’s no problem.

However, it’s these external domain services where we are likely to find the bulk of domain model smells. Through attention to the code smells and refactorings Fowler laid out, we can move towards the concepts of self-consistent aggregate roots with strongly-enforced boundaries.

The double dispatch pattern

It looks like there’s a pattern emerging here around encapsulation, and that’s not an accident. Many of the code smells in the Fowler or Kerievsky refactoring books deal with proper encapsulation of both data and behavior. In the previous post, we looked at closure of operations, that when an operation is completed, the aggregate root’s state is consistent.

In many anemic domain models, the behavior is there but in the wrong place. For the DDD-literate, this is usually in a lot of domain services all poking at the state of the domain model. We can refactor these services to enforce consistency through closed operations on our model, but there are cases where this sort of domain behavior doesn’t belong in the model.

This now begins to be difficult to reconcile. We want to have a consistent model, but now we want to bring in services to the mix. Do we now forgo the concept of Command/Query Separation in our model, and just expose state? Or can we have our cake and eat it too?

Bringing in services

The last example looked at fees, payments and customers. When a payment is recorded against a fee, we re-calculate the balance:

public Payment RecordPayment(decimal paymentAmount)

{

var payment = new Payment(paymentAmount, this);

_payments.Add(payment);

RecalculateBalance();

return payment;

}

private void RecalculateBalance()

{

var totalApplied = _payments.Sum(payment => payment.Amount);

Balance = Amount - totalApplied;

}

The problem comes in when calculating the balance becomes more difficult. We might have a rather complex method for calculating payments, we might have recurring payments, transfers, debits, credits and so on. This might become too much responsibility for the Fee object. In fact, it could be argues that the Fee shouldn’t be responsible for how the balance is calculated, but instead only ensure that when a payment is recorded, the balance is updated.

We have several options here:

- Update the Balance outside the

RecordPaymentmethod, with the caller “remembering” - Use a

BalanceCalculatorservice as part of theRecordPaymentmethod

I never like a solution that requires a user of the domain to “remember” to call a method after another one. It’s not intention-revealing, and tends to leave the domain model in a wacky in-between state. For many domains, this might be acceptable. But with more complexity comes the issue of trying to sort out what scenarios are valid or not. When a test breaks because an invariant is not satisfied, that’s a clear message that something broke the domain.

But if we leave our domain in half-baked states, it becomes much more difficult to decipher what to do when we change the behavior of our model and tests start to break. Are the existing scenarios supported, or are they just around? In the case of the latter, that’s where you start to see more defensive coding practices, throwing exceptions, gut-check asserts and so on.

So we decide to go with the Aggregate Root relying on a Domain Service for balance calculation. Now we have to decide where the service comes from.

For those using a DI container, you might try to inject the dependencies into the aggregate root. That leads to a whole host of problems, which are so numerous I won’t derail a perfectly good post by getting into it. Instead, there’s another, more intention-revealing option: the double dispatch pattern.

Services and the double dispatch pattern

The double dispatch pattern is quite simple. It involves passing an object to a method, and the method body calls another method on the passed in object, usually passing in itself as an argument. In our case, we’ll first create an interface that represents our balance calculator domain service:

public interface IBalanceCalculator

{

decimal Calculate(Fee fee);

}

The signature of the method is important. It accepts a Fee object, but returns the total directly. It doesn’t try to modify the Fee, allowing for a side-effect free function. I can call the calculator as many times as I like with a given Fee, and I can be assured that the Fee object won’t be changed. From the Fee side, I now need to use this service as part of recording a payment:

public Payment RecordPayment(decimal paymentAmount, IBalanceCalculator balanceCalculator)

{

var payment = new Payment(paymentAmount, this);

_payments.Add(payment);

Balance = balanceCalculator.Calculate(this);

return payment;

}

The intent of the RecordPayment method remains the same: it records a payment, and updates the balance. The balance on the Fee object will always be correct. The wrinkle we added is that our RecordPayment method now delegates to a domain service, the IBalanceCalculator, for calculation of the balance. However, the Fee object is still responsible for maintaining a correct balance. We just call the Calculate method on the balance calculator, passing in “this”, to figure out what the actual correct balance can be.

Wrapping it up

When a domain object begins to contain too many responsibilities, we start to break out those extra responsibilities into things like value objects and domain services. This does not mean we have to give up consistency and closure of operations, however. With the use of the double dispatch pattern, we can avoid anemic domain models, as well as the forlorn attempt to inject services into our domain model. Our methods stay very intention-revealing, showing exactly what is needed to fulfill a request of recording a payment.

No silver domain modeling bullets

This past week, I attended a presentation on Object-Role Modeling (with the unfortunate acronym ORM) and its application to DDD modeling. The talk itself was interesting, but more interesting were some of the questions from the audience. The gist of the tool is to provide a better modeling tool for domain modeling than traditional ERM tools or UML class diagrams. ORM is a tool for fact-based analysis of informational models, information being data plus semantics. I’m not an ORM expert, but there are plenty of resources on the web. One of the outputs of this tool could be a complete database, with all constraints, relationships, tables, columns and whatnot built and enforced. However, the speaker, Josh Arnold, mentioned repeatedly that it was not a good idea to do so, or at least it doesn’t scale at all. It could be used as a starting point, but that’s about it.

Several times at the end of the talk, the question came up, “can I use this to generate my domain model” or “database”. Tool-generated applications are a lofty, but extremely flawed goal. Code generation is interesting as a one-time, one-way affair. But beyond that, code generation does not work. We’ve seen it time and time again. Even though the tools get better, the underlying invalid assumption does not change. The fundamental problem is that visual code design tools can never and will never be as expressive, flexible and powerful as actual code. There will always be a mismatch here, and it is a fool’s errand to try to build anything more. Instead, the ORM tool looked quite useful as a modeling tool for generating conversation and validating assumptions about their domain, rather than a domain model builder.

Ultimately, the only validation that our domain is correct is the working code. There is no silver bullet for writing code, as there is always some level of complexity in our applications that requires customization. And there’s nothing that codegen tools hate more than modification of the generated code However, I’m open to the idea that I’m wrong here, and I would love to be shown otherwise.

10 Lessons from a Long Running DDD Project

Round about 7 years ago, I was part of a very large project which rooted its design and architecture around domain-driven design concepts. I’ve blogged a lot about that experience (and others), but one interesting aspect of the experience is we were afforded more or less a do-over, with a new system in a very similar domain. I presented this topic at NDC Oslo (recorded, I’ll post when available).

I had a lot of lessons learned from the code perspective, where things like AutoMapper, MediatR, Respawn and more came out of it. Feature folders, CQRS, conventional HTML with HtmlTags were used as well. But beyond just the code pieces were the broader architectural patterns that we more or less ignored in the first DDD system. We had a number of lessons learned, and quite a few were from decisions made very early in the project.

Lesson 1: Bounded contexts are a thing

Very early on in the first project, we laid out the personas for our application. This was also when Agile and Scrum were really starting to be used in the large, so we were all about using user stories, personas and the like.

We put all the personas on giant post-it notes on the wall. There was a problem. They didn’t fit. There were so many personas, we couldn’t look at all of them at one.

We put all the personas on giant post-it notes on the wall. There was a problem. They didn’t fit. There were so many personas, we couldn’t look at all of them at one.

So we color coded them and divided them up based on lines of communication, reporting, agency, whatever made sense.

Well, it turned out that those colors (just faked above) were perfect borders for bounded contexts. Also, it turns out that 72 personas for a single application is way, way too many.

Lesson 2: Ubiquitous language should be…ubiquitous

One of the side effects of cramming too many personas into one application is that we got to the point where some of the core domain objects had very generic names in order to have a name that everyone agreed upon.

We had a Person object, and everyone agreed what “person” meant. Unfortunately, this was only a name that the product owners agreed upon, no one else that would ever use the system would understand what that term meant. It was the lowest common denominator between all the different contexts, and in order to mean something to everyone, it could not contain behavior that applied to anyone.

When you have very generic names for core models that aren’t actually used by any domain expert, you have something worse than an anemic domain model - a generic domain model.

Lesson 3: Core domain needs consensus

We talked to various domain experts in many groups, and all had a very different perspective on what the core domain of the system was. Not what it should be, but what it was. For one group, it was the part that replaced a paper form, another it was the kids the system was intending to help, another it was bringing those kids to trial and another the outcome of those cases. Each has wildly different motivations and workflows, and even different metrics on which they are measured.

Beyond that, we had directly opposed motivations. While one group was focused on keeping kids out of jail, another was managing cases to put them in jail! With such different views, it was quite difficult to build a system that met the needs of both. Even to the point where the conduits to use were completely out of touch with the basic workflow of each group. Unsurprisingly, one group had to win, so the focus of the application was seen mostly through the lens of a single group.

Lesson 4: Ubiquitous language needs consensus

A slight variation on lesson 2, we had a core entity on our model where at least the name meant something to everyone in the working group. However, that something again varied wildly from group to group.

For one group, the term was in reference to a paper form filed. Another, something as part of a case. Another, an event with a specific legal outcome. And another, it was just something a kid had done wrong and we needed to move past. I’m simplifying and paraphrasing of course, but even in this system, a legal one, there were very explicit legal definitions about what things meant at certain times, and reporting requirements. Effectively we had created one master document that everyone went to to make changes. It wouldn’t work in the real world, and it was very difficult to work in ours.

Lesson 5: Structural patterns are the least important part of DDD

Early on we spent a ton of time on getting the design right of the DDD building blocks: entities, aggregates, value objects, repositories, services, and more. But of all the things that would lead to the success or failure of the project, or even just slowing us down/making us go faster, these patterns were by far the least important.

That’s not to say that they weren’t valuable, they just didn’t have a large contribution to the success of the project. For the vast majority of the domain, it only needed very dumb CRUD objects. For a dozen or so very particular cases, we needed highly behavioral, encapsulated domain objects. Optimizing your entire system for the complexity of 10% really doesn’t make much sense, which is why in subsequent systems we’ve moved towards a more CQRS model, where each command or query has complete control of how to model the work.

With commands and queries, we can use pretty much whatever system we want – from straight up SQL to event sourcing. In this system, because we focused on the patterns and layers, we pigeonholed ourselves into a singular pattern, system-wide.

In the first project, we targeted everyone that could possibly be involved with the overall process. This wound up to be a dozen state agencies and countless other groups and sub-groups. Quite a lot of contention in the model (also a great reason why you can never have a single master data model for an entire enterprise). We felt good about the software itself – it was modular and easy to extend, but the domain model itself just couldn’t satisfy all the users involved, only really a subset.

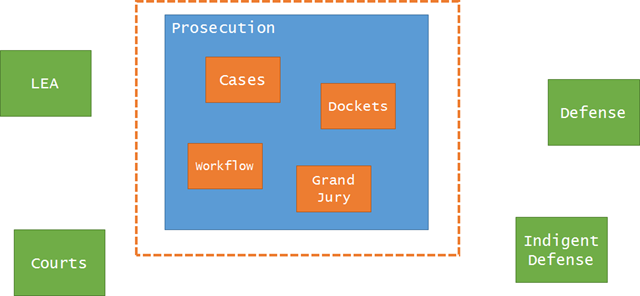

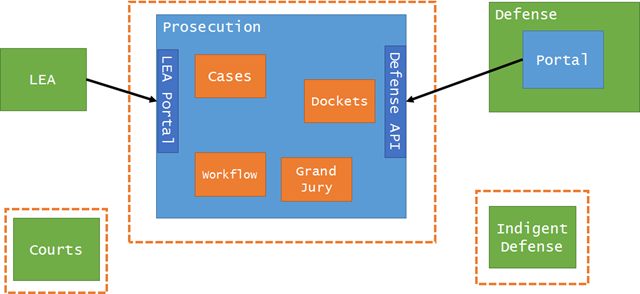

The second project targeted only a single aspect of the original overall legal process – the prosecution agency. Targeting just a single group, actually a single agency, brought tremendous benefits for us.

Lesson 6: Cohesiveness brings greater clarity and deeper insight

Our initial conversations in the second project were somewhat colored by our first project. We started with an assumption that the core focus, the core domain would be at least the same as the monolith, but maybe a different view of it. We were wrong.

In the new version of the app, the entire focus of the system revolves around “cases”. I know, crazy that an app built for the day-to-day functions of a prosecution agency focuses centrally on a case:

Once we settled on the core domain, the possibilities then greatly opened up for modeling around that concept. Because the first app only tangentially dealt with cases (there wasn’t even a “Case” in the original model), it was more or less an impedance mismatch for its users in the prosecution agency. It was a bit humbling to hear the feedback from the prosecutors about the first project.

But in the second project, because our core domain was focused, we could spend much more time modeling workflows and behaviors that fit what the prosecution agency actually needed.

Lesson 7: Be flexible where you need to, rigid in others

Although we were able to come to a consensus amongst prosecution agencies about what a case was, what the key things you could DO with a case were and the like, we couldn’t get any consensus about how a case should be managed.

This makes a lot of sense – the state has legal reporting requirements and the courts have a ton of procedural rules, but internal to an agency, they’re free to manage the work any way they wanted to.

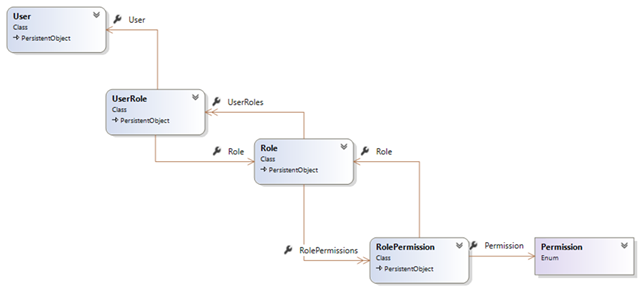

In the first system, roles were baked in to the system, causing a lot of confusion for counties where one person wore many different hats. In the new system, permissions were hard-coded against tasks, but not roles:

The Permission here is an enum, and we tied permissions to tasks like “Approve Case” and “Add Evidence” and “Submit Disposition” etc. Those were directly tied to actions in our application, and you couldn’t add new permissions without modifying the code.

Roles (or groups, whatever) were not hardcoded, and left completely up to each agency how they liked to organize their work and decide who can do what.

With DDD it’s important to model both the rigid and flexible, they’re equally important in the overall model you build.

Lesson 8: Sometimes you need to invent a model

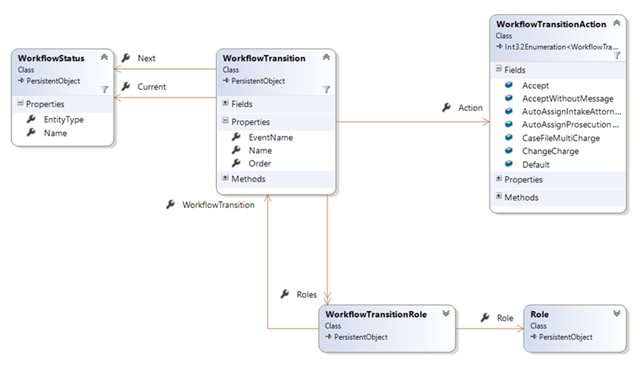

While we were able to model quite well the actions one can perform with an individual case, it was immediately apparent when visiting different county agencies that their workflows varied significantly inside their departments.

This meant we couldn’t do things like implement a workflow internal to a case itself – everyone’s workflow was different. The only thing we could really embed were procedural/legal rules in our behaviors, but everything else was up for grabs. But we still wanted to manage workflows for everyone.

In this case, we needed to build consensus for a model that didn’t really exist in each county in isolation. If we focused on a single county, we could have baked the rules about how a case is managed into their individual system. But since we were building a system across counties, we needed to build a model that satisfied all agencies:

In this model, we explicitly built a configurable workflow, with states and transitions and security roles around who could perform those transitions. While no individual county had this model, it was the meta-model we found while looking across all counties.

Lesson 9: Don’t blindly follow pattern advice

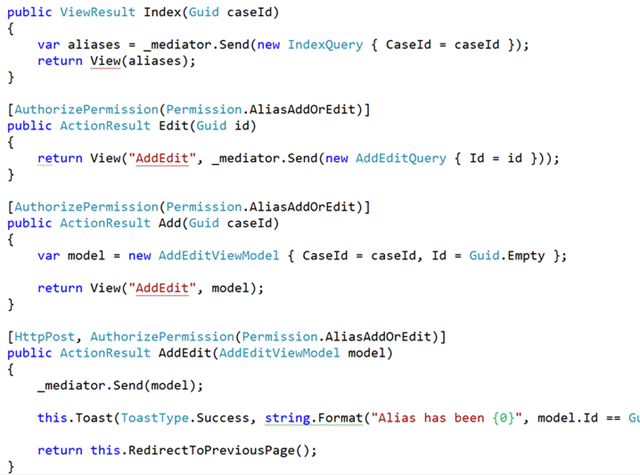

In the new app, I performed an experiment. I would only add tools, patterns, and libraries when the need presented itself but no sooner. This meant I didn’t add a repository, unit of work, services, really anything until an actual pain surfaced. Most of the DDD books these days have prescriptive guidance about what your domain model should look like, how you should do repositories and so on, but I wanted to see if I could simply arrive at these patterns by code smells and refactoring.

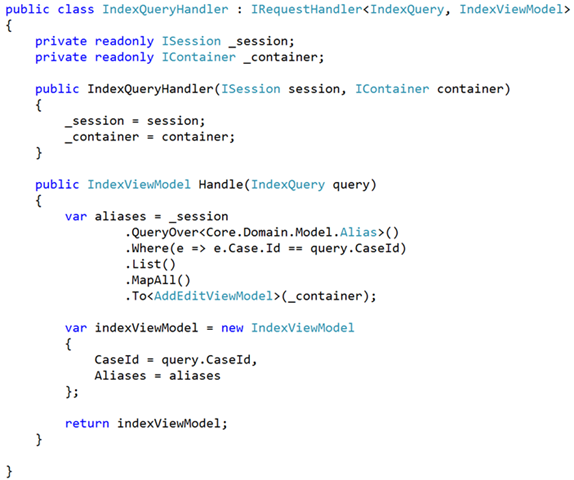

The funny thing is, I never did. We left out those patterns, and we never found a need to put them back in. Instead, we drove our usage around CQRS and the mediator pattern (something I’ve used for years but finally extracted our internal usage into MediatR. Instead, our controllers were pretty uniform in their appearance:

And the handlers themselves (as I’ve blogged about many times) were tightly focused on a single action, with no need to abstract anything:

I’ve extended this to other areas of development too, like front-end development. It’s actually kinda crazy how far you can get without jQuery these days, if you just use lodash and the DOM.

Lesson 10: Microservices and anti-corruption layers are your friend

There is a downside to going to bounded contexts and away from the “majestic monolith”, and that’s integration. Now that we have an application solely dealing with one agency, we have to communicate between different applications.

This turned out to be a bit easier than we thought, however. This domain existed well before computers, so the interfaces between the prosecution and external parties/agencies/systems was very well established.

This was also the section of the book skipped the most, around anti-corruption layers and bounded contexts. We had to crack open that section of the book, dust it off, smell the smell of pages never before read, and figure out how we should tackle integration.

We’ve quite a bit of experience in this area it turns out, so it was really just a matter of deciding for each 3rd party what kind of integration would work best.

For some 3rd parties, we could create an entirely separate app with no integration. Some needed a special app that performed the translation and anti-corruption layer, and some needed an entirely separately deployed app that communicated to our system via hypermedia-rich REST APIs.

Regardless, we never felt we had to build a single solution for all involved. We instead picked the right integration for the job, with an eye of not reinventing things as we went.

Conclusion

In both cases, I’d say both our systems were successful, since they shipped and are both being used and extended to this day. With the more tightly focused domain in the second system we were able to achieve that “greater insight” that the DDD book talks about.

In case anyone wonders, I intentionally did not talk about actors or event sourcing in this series – both things we’ve done and shipped, but found the applicability to be limited to inside a bounded context (or even more typically, a corner of a bounded context). Another post for another day!